A Moment of Grace: In Praise of Black Girl Arrogance

[Note: This essay was published, with photographs, November 2015 at my previous blog, Glamourtunist.com. Photos have been updated, text remains as originally published. ]

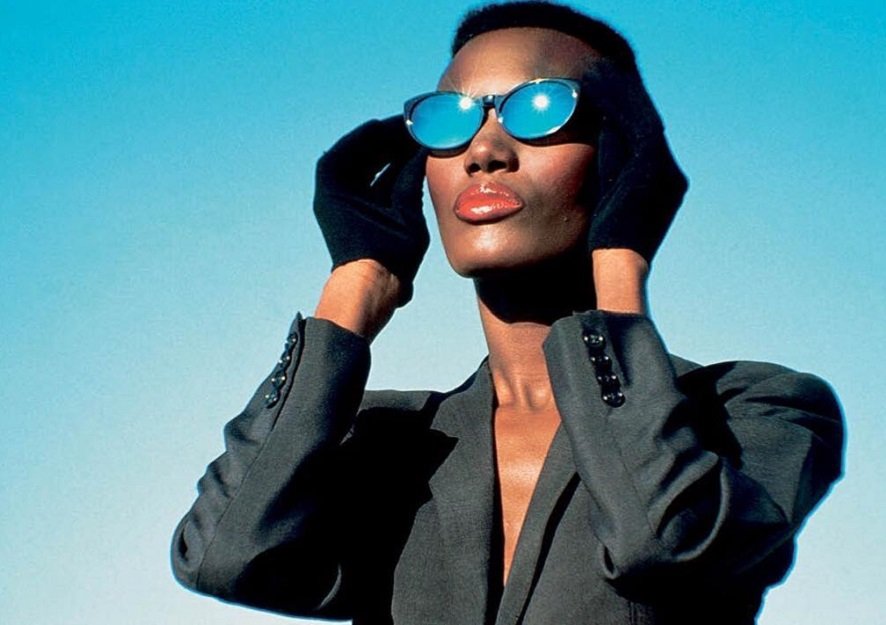

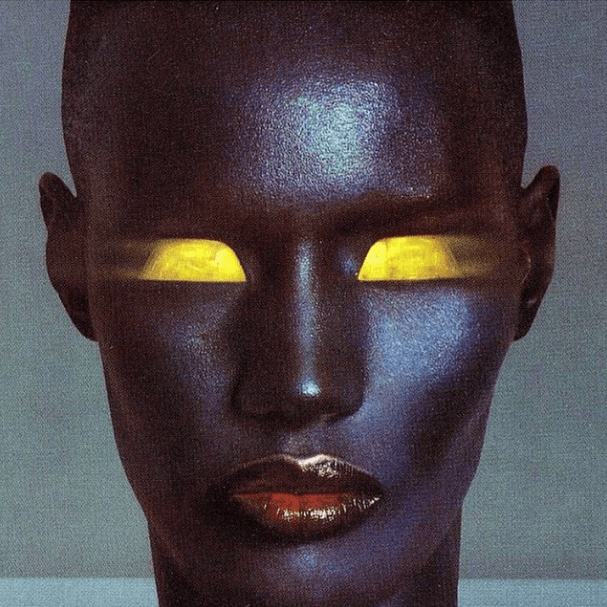

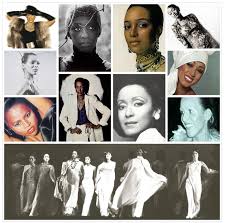

This Grace is sufficient. Maybe she inspired you to become more flexible so you, too, could bend and contort yourself into a scene of “Island Life.” Or, perhaps she hula-hooped you into a trance, moving the cylindrical toy around her waist as she, mic in hand, belted out one of her popular songs. It could very well be her legendary beauty – her fierceness piercing the still life of every photo she has taken, or her masterful, delicious storytelling in her recently released memoirs. In whatever incarnation you encountered Grace Jones, you, like me, are likely to have gotten your life, or multiple lives because Grace slays you and you are reborn. Grace is reincarnation.

Grace Jones represents the very best of so many aesthetically sublime and delicious possibilities and realizations for global fashion and popular culture. In addition to her album covers, music videos, and fashion editorials, she is etched into our minds through so many other moments: her role of eccentric fashion model Strangé in the 1992 film “Boomerang”; any one of the many photos of her live performances in her decades long career, such as a 1987 performance where she collaborated with artist Keith Haring for her stage costume; and her memorable runway walks such as at the Summer 1988/89 Patrick Kelly show in Paris, where she walked the runway dressed in a black bathing suit and cape adorned with an applique of neon stars and planets, red tights, a bustle of individual scarves of various colors hanging from her waste, and a hat with a long white ponytail hanging out of the top. In each of these moments and so many more, the camera shutter opens and closes on her to fulfill the promise, play, and pulchritude of every single image she has created. Her visual and performance archive is always embodying and emboldening the radical potential of fashion, music, dance, performance art and photography for exploding the neat boundaries built around race, gender, sexuality, time, and space from one moment to the next. Grace is divine.

The icon and iconography of Grace Jones emerges as a clear archive of Black girl arrogance in all its fashionable fierceness and intervention. Black girl arrogance refers to both a spirit and embodiment of intelligent, beautiful, desirable, fierce daring that Black girls and women represent – whether on the runway or in the streets, in the classroom or the boardroom, at the piano or behind the podium – that makes their presence known in a social, political, cultural context or milieu that would rather render them unknown. It is thus at times an organic way of being, and in other moments a chosen tactic, that is always and already for one’s self. Sometimes that arrogance is refusing the gaze and living one’s life, and still other times it demands of you, “see me.” The fact that anyone else gets to witness this divinity is, well, grace. And I return to Grace Jones here to give her the respect she so deserves, but also because it is through returning to Grace that I believe Black girl arrogance, in all of its complexities and genius, is re-membered for now and for what is to come.

The icon and iconography of Grace Jones emerges as a clear archive of Black girl arrogance in all its fashionable fierceness and intervention. Black girl arrogance refers to both a spirit and embodiment of intelligent, beautiful, desirable, fierce daring that Black girls and women represent – whether on the runway or in the streets, in the classroom or the boardroom, at the piano or behind the podium – that makes their presence known in a social, political, cultural context or milieu that would rather render them unknown. It is thus at times an organic way of being, and in other moments a chosen tactic, that is always and already for one’s self. Sometimes that arrogance is refusing the gaze and living one’s life, and still other times it demands of you, “see me.” The fact that anyone else gets to witness this divinity is, well, grace. And I return to Grace Jones here to give her the respect she so deserves, but also because it is through returning to Grace that I believe Black girl arrogance, in all of its complexities and genius, is re-membered for now and for what is to come.

For instance, Black girl arrogance has once again been made legible at the intersections of fashion and style with television, film, and music. We saw it just recently in Emmy-nominated actress and transgender activist Laverne Cox’s stunning photos in Allure Magazine, and in her many other moments including her picture on a 2014 cover of Time Magazine. We see it in Academy Award-winner Lupita Nyong’o’s boundary breaking and trendsetting beauty and glamour, which has completely raised the bar for red carpets all over the globe. We see it in Solange Knowles’ epic wedding photo, which flooded our Facebook newsfeeds, Twitter timelines, and Instagram pages with panoramic shots of gorgeous Black women adorned in radiant ivory gowns, and effecting the etherealness of any dream we wish would come true. And where Solange leaves us dreaming, big sister Beyoncé made “I woke up like this” the mantra of every bold and brilliant person ready to declare that who I am and how I am is already “Flawless.” The 2015 “Black Girls Rock” award show that aired on BET and Centric offered numerous examples of Black girl arrogance as intervention in many of the speeches including those by singer Erykah Badu, educator Nadia Lopez, FLOTUS Michelle Obama, Dr. Helene Gayle, and actress Jada Pinkett Smith. What about Rihanna’s recent performance of “Bitch Better Have My Money” at the #iHeartRadio Awards? The performance included many elements of power moments from the archive of Black women international pop star performances, from Lil’ Kim’s green wig and furs in the video for her 90s hit “Crush On You” to Diana Ross’s epic exiting of the superbowl halftime show in a helicopter that descended on the stage to whisk her away (also reminiscent of Grace Jones’ Strangé’s epic arrival in “Boomerang” via helicopter, and then a chariot driven by men). Here Rihanna’s daring is part of a continuum in her performances of Black girl arrogance, including her homage to Josephine Baker on the occasion of the legendary performer’s birthday at the red carpet of the 2014 CFDA Awards, where Rihanna was clad in a transparent bosom bearing silver beaded gown and bejeweled headdress. For Black women performers and Black girl arrogance, the archive and the ancestry matters. Grace matters.

It is imperative to note the historical antecedents for Grace Jones – the eccentric freedom of Eartha Kitt, the elegance and sophistication of Lena Horne and Ruby Dee, and the beauty folk ways of Maya Angelou and Cicely Tyson most come to mind. Another historical antecedent that demonstrates Black girl arrogance, and laid important roots for Grace Jones to later help define and then defy boundaries around Blackness and femininity, appears in the wonderful documentary Versailles ’73: An American Revolution. The documentary examines the legendary battle at Versailles fashion face-off between five American and five Parisian design houses, a tale examined in greater depth in the new book The Battle of Versailles: The Night American Fashion Stumbled into the Spotlight and Made History by Pulitzer Prize-winning Washington Post fashion critic Robin Givhan. Among the points made by several of the interviewees that appear in Versaille ‘73, including legendary fashion model and editor China Machado, fashion historian Barbara Summers, and fashion and beauty editor Mikki Taylor, was that the success of the American presentation at that show was the presence of Black models Norma Jean Darden, Pat Cleveland, Bethann Hardison, and so many others, whose walk of “affirmation” to quote Taylor, was what set the American show apart from the Parisian set.

While Taylor’s observation about the impact of the Black models affirmative stance is in itself a rich one to engage, I look at that moment, at Grace, and the intersections of fashion and identity and submit that amongst the gems that Black models brought (and still bring) to the runway was something that is actually in excess of “affirmation”: Black girl arrogance. This Black girl arrogance, though embedded in the very movement and being-ness of the Black models at the ’73 show at Versailles is so missing from the runways of today’s fashion shows in the lack of racial ethnic diversity, as rightfully noted in the 2014 open letter of protest authored by Hardison, and models Iman and Naomi Campbell. A black girl arrogance that haunts us when we remember the days of fashion past, and are reminded of the disappeared characteristic of personality that was once an essential ingredient to the development of a signature walk and presence on the runways for any model, Black or otherwise.

While Taylor’s observation about the impact of the Black models affirmative stance is in itself a rich one to engage, I look at that moment, at Grace, and the intersections of fashion and identity and submit that amongst the gems that Black models brought (and still bring) to the runway was something that is actually in excess of “affirmation”: Black girl arrogance. This Black girl arrogance, though embedded in the very movement and being-ness of the Black models at the ’73 show at Versailles is so missing from the runways of today’s fashion shows in the lack of racial ethnic diversity, as rightfully noted in the 2014 open letter of protest authored by Hardison, and models Iman and Naomi Campbell. A black girl arrogance that haunts us when we remember the days of fashion past, and are reminded of the disappeared characteristic of personality that was once an essential ingredient to the development of a signature walk and presence on the runways for any model, Black or otherwise.

I am convinced that whether or not uniqueness and personality were ever embraced, Grace Jones would still be who she was and is. What other way was there for her to be? Still, in the way that she pushes us beyond our comfort zones, and shows us what it means to create a path for one’s self through an ethos of having no fucks to give, the existence of Grace Jones and all she has meant is priceless. Here’s hoping the next era of fashion and popular culture will applaud and embrace these moments of productive defiance like the Black girl arrogance revival of which I write, on the runways, in ad campaigns, and at the head of design houses and fashion magazines. Clearly television has received the memo, as evident in shows headed by defiant, brilliant, Black women are at the top of the ratings and lording over the zeitgeist of popular culture, from Kerry Washington’s portrayal of Olivia Pope on “Scandal” and Gabrielle Union’s Mary Jane Paul on BET’s “Being Mary Jane,” to Viola Davis’s multilayered Professor Annalise Keating on ABC’s “How to Get Away With Murder,” and most recently, leading the pack is Taraji P. Henson’s critically acclaimed and popularly adored Cookie Lyon on Fox’s juggernaut “Empire.” It is the very thing that seems to revive the very lifeblood of this global industry and persists in fashioning a future. No matter what, Grace Jones, her predecessors and descendants will carry on being their fierce self. They woke up like this.